SKIN CANCER FACT SHEET

There are 3 main types of skin cancers

-

Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC)

-

Squamous Cell Carcinoma ( SCC)

-

Melanoma

There are also a number of “premalignant”conditions which if unrecognised and untreated have a risk of progressing to a malignant cancer.

These include

-

Keratoacanthomas

-

Actinic keratosis

-

Bowen’s Disease

Keratoacanthoma (KA) is a common low-grade (unlikely to metastasize or invade) skin tumourthat is believed to originate from the neck of the hair follicle. KA is commonly found on sun-exposed skin, and often is seen on the face, forearms and hands.

The defining characteristic of KA is that it is dome-shaped, symmetrical, surrounded by a smooth wall of inflamed skin, and capped with keratin scales and debris. It always grows rapidly, reaching a large size within days or weeks. Many keratoacanthomas shrink or even go away on their own over time without any treatment, but some continue to grow, and a few may even spread to other parts of the body. Their growth is often hard to predict, so many skin cancer experts consider them a type of squamous cell skin cancer and treat them as such.

Actinic keratosis (solar keratosis)

Actinic keratosis, also known as solar keratosis, is a pre-cancerous skin condition caused by too much exposure to the sun. Actinic keratoses are usually small (less than 8 mm across), rough or scaly spots that may be pink-red or flesh-colored. Usually they start on the face, ears, backs of the hands, and arms of middle-aged or older people with fair skin, although they can occur on other sun-exposed areas. People who have them usually develop more than one. Actinic keratoses tend to grow slowly and usually do not cause any symptoms (although some might be itchy or sore). They sometimes go away on their own, but they may come back.

In some cases, actinic keratoses may turn into squamous cell cancers. Most actinic keratoses do not become cancers, but it can be hard sometimes for doctors to tell these apart from true skin cancers, so doctors often recommend treating them. If they are not treated, you and your doctor should check them regularly for changes that might be signs of skin cancer.

Bowen’s Disease (Squamous Cell Carcinoma “in situ”)

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ, also called Bowen disease, is the earliest form of squamous cell skin cancer. “In situ” means that the cells of these cancers are still only in the epidermis and have not invaded the dermis.

Bowen disease appears as reddish patches. Compared with actinic keratoses, Bowen disease patches tend to be larger (sometimes over 1cm across), redder, scalier, and sometimes crusted. Like actinic keratosis, it usually does not cause any symptoms, although it might be itchy or sore.

Bowen’s disease ( BD) typically presents as a gradually enlarging, well- demarcated reddened plaque with an irregular border and surface crusting or scaling. BD may occur at any age in adults, but is rare before the age of 30 years; most patients are aged over 60. Any site may be affected, although involvement of palms or soles is uncommon. BD occurs predominantly in women (70-85% of cases). About 60-85% of patients have lesions on the lower leg, usually in previously or presently sun-exposed areas of skin. Bowen disease can also occur in the skin of the anal and genital areas.

This is often related to sexually transmitted infection with human papilloma viruses (HPVs), the viruses that can also cause genital warts.

Causes of Bowen’s disease include solar damage, arsenic, immunosuppression (including AIDS), viral infection (human papillomavirus or HPV) and chronic skin injury and dermatoses.

Most studies report a risk of progression to invasive SCC at 3 to 5 per cent. Because of this risk of progression, doctors usually recommend treating them. People who have these are also at higher risk for other skin cancers, so close follow-up with a doctor is important.

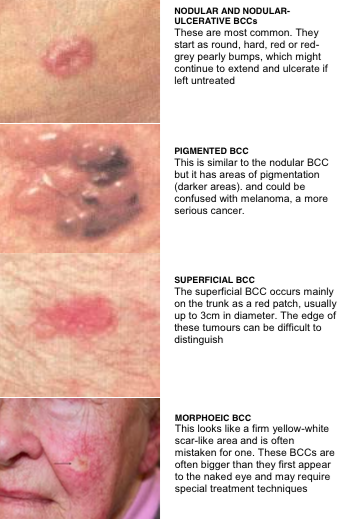

Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinomas – BCCs and SCCs

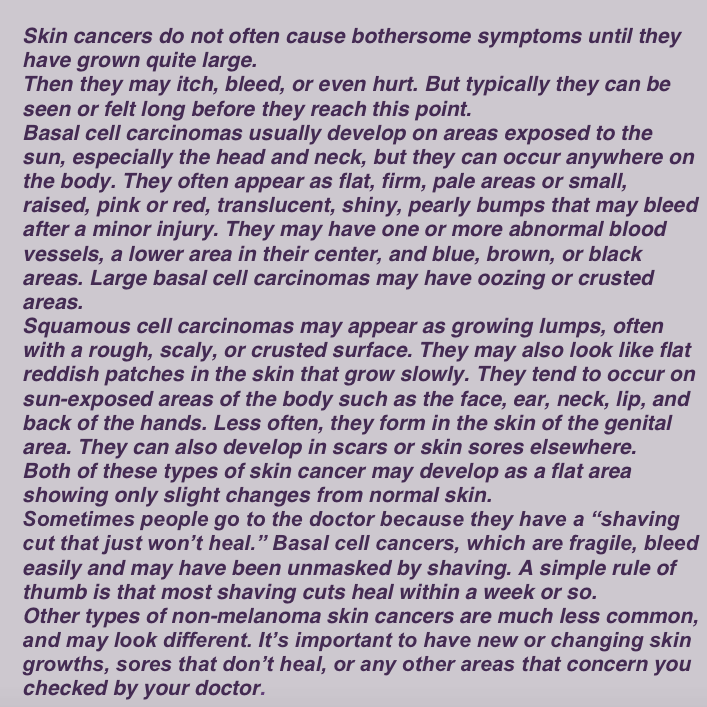

Signs and Symptoms of Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC)

BCCs are the single most common malignant cancers of the skin. BCCs grows from cells in the lower part of the upper layer of the skin. They occur most often after the age of 40. Although sun exposure is an important cause of BCC’s, other factors, such as ethnicity and skin type, play a role in its aetiology or causation. It seems that intermittent, as opposed to cumulative, sun exposure is the more prominent factor in the development of BCCs.

BCCs most commonly appear on the face, head, neck and trunk regions and can occur in difficult to treat areas such as near the eye and the lower legs. Approximately 80 per cent of all cases of basal cell cancers (BCCs) are found on the head and neck, the nose being a common site.

Clinically, BCCs appear as pink or white pearly papules with areas of telangiectasia. As lesions progress, they may ulcerate and look as if they have been gnawed upon: the classic “rat bite” description.

Risk factors include poor ability to tan, fair skin, immunosuppression, old age, and exposure to UV radiation.

There are also a number of inherited skin disorders associated with the development of BCCs, such as Gorlin’s syndrome. Gorlin’s syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition, meaning that half of an affected person’s children also have the syndrome. It may affect one in every 50,000 people. These patients present with multiple BCCs from an early age.

The growth tends to be quite slow, taking a period of months to years.

BCCs grow by direct extension; therefore, the incidence of metastasis ( spread to distant sites) is low.

Diagnosis is made only from biopsy.

Although they are rarely a threat to life, if left untreated they can grow, erode and destroy adjoining structures. Loss of whole organs, such as the nose, ear and eye, can occasionally occur. BCC’s are more easily and successfully treated in their early stages. The larger the tumour the more extensive the treatment required. In most cases they are curable and one can achieve excellent cosmetic results.

Treatment options for BCCs include electrodessication and curettage, surgical excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, or radiation therapy for elderly patients who cannot tolerate surgical procedures.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)

The second most common form of skin cancer is the SCC. It may grow much faster than a BCC. SCC’s may occasionally spread throughout the body (metastasize). SCCs usually form a scaly, quickly growing pink lump or wart-like growth, which may also break down, crust, bleed and ulcerate. They do not usually cause pain but may be tender, or cause a burning or stinging sensation. They most commonly occur on areas exposed to a lot of sunlight such as the face, ears, (bald) scalp, lips and backs of the hands. They also occur on mucous membranes such as on the tongue and inside the mouth.

Considerations for suspecting SCC are:

-

Rapid recent growth.

-

Elevated lesion, on removal of scale.

-

Bleeding and/or ulcération.

-

Unresolving lesions on the lips.

-

An SCC can present as an ulcerated lesion and vary in size from a few millimetres to several centimetres in diameter.

Sometimes they grow to the size of a pea or larger in a few weeks, though more commonly they grow slowly over months or years. SCCs have a greater potential for metastasis than BCC’s. The risk of metastasis depends on a multitude of factors including location of the primary lesion, immune status, size of tumor, degree of differentiation on histopathology ( microscope) examination, and depth of invasion. Occurrence is related to chronic sun exposure and is seen in sun-damaged and fair skin.

Individuals with previous chronic wounds, burns and leg ulcers can also develop into SCCs, termed as Marjolin’s ulcers.

People who have had organ transplants, or medications to suppress their immune system for other reasons, are at higher risk of developing SCCs. In transplant patients SCCs are also more likely to grow quickly and spread throughout the body.

This makes regular skin checks and early treatment of skin cancers extremely important for people who have had transplants or have suppressed immune systems for other reasons.

Inflammatory skin diseases such as lichen sclerosus and epidermolysis bullosa can also predispose development of SCCs.

Smoking also appears to be a risk factor for SCCs with it being more than twice as likely in those who have smoked for 20 or more years compared to non- smokers.

Examples SCC’s

Treatment entails electrodessication and curettage, surgical excision, or Mohs micrographic surgery. SCCs are generally treated by surgical excision. Non-surgical options for the treatment of cutaneous SCC include topical chemotherapy, topical immune response modifiers, PDT, radiotherapy and systemic chemotherapy.

Topical therapy, such as imiquimod cream and PDT, is generally limited to premalignant (AKs) and in situ lesions (Bowen’s).

Melanoma

Melanomas are less common than BCCs and SCCs, but a much more dangerous skin cancer.

Melanoma is classed as a malignant tumour of melanocytes. Melanocytes produce the dark pigmentcalled melanin responsible for the colour of skin. Melanocytes are predominantly in the skin,but are also situated in other parts of the body, such as the bowel and the eye. This means that melanoma may occur in any area where melanocytes occur.

Malignant melanoma (MM) is the most life threatening of all skin cancers. MM is seen more in women than men and one fifth of cases occur in young adults.

The lower leg and back are common sites of MMs.

Exposure to UV light is considered to be responsible for between 65 and 95 per cent of cases but melanoma demonstrates a less clear-cut relationship with sun exposure. Unlike BCCs, melanoma does not typically appear on skin that has received the most cumulative UVR.

Furthermore, melanoma has a peak incidence in younger patients, who have acquired less lifetime sun exposure than their elderly counterparts. Melanoma occurs more frequently in people who work indoors, as opposed to outdoors. One proposed explanation for why indoor workers have a higher incidence of melanoma is that melanoma may be related to intense, intermittent sun exposure of untanned skin.

This also supports the distribution pattern of melanoma seen on the trunk in men and lower extremities in women.

Like SCCs and BCCs, melanomas can occur on exposed skin, but they also occur on skin that is generally covered, but which has been sunburnt in the past. Malignant melanomas may spread throughout the body and cause death. Metastasis (spread to distant sites) of early melanomas is possible, but less than one fifth of early diagnosed melanomas become metastatic.

Brain metastases are particularly common in patients with metastatic melanoma Malignant melanomas may spread throughout the body and cause death. Melanomas either develop from an existing mole or appear as a new brown, red or black spot which changes and grows in size. Melanomas usually pass through an initial flat phase which is not significantly life-threatening and is generally curable by having it cut out.

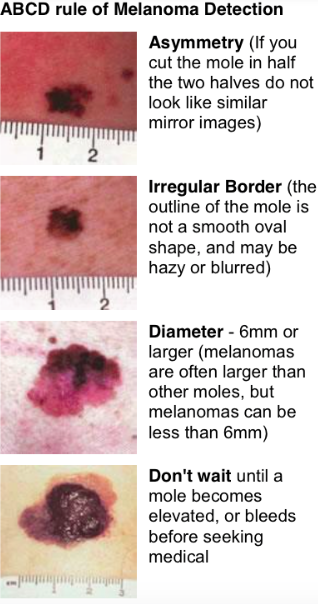

Melanomas distinguish themselves from moles by changing. The changes occur in size (enlargement), shape or colour (usually all three). That is, melanomas get larger, more irregular in shape and most often darker and more uneven in colour.

If the mole is symptomatic this is also considered a significant potential diagnostic sign; the mole may itch, ulcerate or bleed. Other changes are specified for the most dangerous form of melanoma, nodular melanoma which also includes changes of elevation above the skin surface.

The changes of melanoma are generally detectable over a period of months. Changes that develop over days are almost always due to inflammation or injury and it is appropriate to wait for a week or two to allow sudden changes to go away. If the change fails to revert to normal and continues for more than a month you should see your doctor.

Normal moles usually resemble one another, a different looking mole should be reviewed by your doctor. A new mole after the age of 25 should also be reviewed by your doctor.

Melanomas will generally reach a size that is noticeably larger than most other moles (>6mm) without developing serious life-threatening potential. By this time they will usually show uneven colour and irregular shape.

A helpful guideline to distinguish melanomas from benign nevi (moles) is the ABCD rule. Melanoma tends to be Asymmetrical, with Border irregularity, Colour variegation, and a Diameter greater than 6 mm.

This is, of course, just a clinical tool and does not help in the diagnosis of all melanomas.

Some melanomas do not show the features mentioned above. Some are lumpy right from the start. Others have little or no brown pigment and appear as reddish patches or like blood blisters. Not all melanomas are 6mm or greater in size.

Uncommonly they will develop in non-sunexposed areas such as the scalp, palms or soles or under finger or toe nails.

What are the Risk factors for Melanoma?

Growing up in Australia is a risk factor itself for developing melanoma. Exposure to UV light is considered to be responsible for between 65 and 95 per cent of cases.

Other risk factors for melanoma include

-

a first-degree relative with melanoma,

-

the presence of multiple atypical or dysplastic nevi ( moles)

-

fair skin and light eyes,

-

a history of severe childhood sunburns,

-

a history of Non melanoma skin cancer

Changing moles, or moles that look different from the other moles on the patient, are two other clinical clues that should be considered.

Your dermatologist can advise you about your melanoma risk.

There are four major clinicohistopathologic subtypes:

-

superficial spreading,

-

lentigo maligna,

-

nodular, and

-

acral lentigines.

DiagnosisThe diagnosis of melanoma is generally made from biopsy ( taking a piece) or removal of a skin lesion. Pigmented lesions should not be burnt or frozen as this may mask a malignant melanoma.

Under the microscope, melanomas appear as clusters of large and atypical melanocytes with visible mitotic figures proliferating above the epidermis.

The pathology report will include the Breslow’s depth (full tumour thickness) and the presence or absence of ulceration.

The depth of the lesion is the strongest histologic factor influencing prognosis (outlook or survivability)

Wide local excision is the only acceptable treatment and surgical margins are determined by Breslow’s depth and the diameter of the lesion to ensure adequate removal of all the tumour.

Alpha- Interferon therapy may be considered for adjuvant ( additional) therapy in certain cases.

Melanomas, especially the deeper ones, are frequently lethal; they are responsible for 75% of skin cancer deaths.